Dark Artistry: Anatomical Drawings as Memento Mori Art

- gothpersona

- Jun 27

- 8 min read

Humans have always been fascinated with the inner workings of our own bodies–some of the first musical instruments were flutes made of human bone. This thirst for knowledge about the body and its mysteries has led artists and scientists alike to spend hours closely studying the bones, muscles, veins, organs, and nerves that make up our earthly vessels.

For the sake of advancing medical knowledge, it was essential to have accurate representations of the body so physicians could learn from them. In the eras before photography, creating these images was the province of skilled artists. Medical illustrations from the Renaissance through the 19th century often combine anatomical detail with an artist’s eye for beauty and composition, resulting in captivating images that are macabre yet strangely moving. Like the memento mori paintings of European art history, they remind us that we live in our bodies–and those bodies are subject to disease and decay.

Let’s explore some of these beautifully bizarre vintage anatomical drawings, and how they express the memento mori theme while showing the delicate inner workings of the human form.

What is memento mori art?

Before delving into the world of anatomical art, we should define the term memento mori and how it fits into art history. “Memento mori” is a Latin phrase meaning “remember you must die.” It refers to artwork, usually depicting skulls or skeletons, that is meant to remind the viewer of their own mortality. Memento mori art flourished in Europe from the Middle Ages through the 17th century, taking several different forms. It was linked to the Christian idea that the life of the body is fleeting and the faithful should focus instead on their souls, repenting and putting aside worldly concerns.

One example of this theme is the vanitas (vanity) paintings popular in the Netherlands and surrounding areas that reached the height of their popularity in the 1600s. These took the form of still lifes featuring skulls and other objects meant to evoke the idea that life is temporary, such as watches, bubbles, hourglasses, and extinguished candles.

Another example of the memento mori in art is the danse macabre motif. Appearing frequently in paintings, murals, and tapestries, it shows groups of dancing skeletons. Often the figures play musical instruments like pipes or drums and hold hands with living humans, drawing them away into death. These images often show people from all walks of life, such as royalty, clergymen, and peasants linking arms with each other and skeletons or the Grim Reaper, symbolizing that all people are equal in death. Danse macabre imagery is commonly associated with the Black Death. It was also humorous and satirical, poking fun at the idea of human hierarchies that were as ephemeral as dust.

With the coming of the Renaissance starting in Italy in the late 15th century, secularism and science began to enter public discourse and influence ideas about the body and the mind. As the Church’s stranglehold on politics and philosophy began to ease, scientists and physicians turned to the study of human anatomy with renewed vigor. Renowned artists like Da Vinci drew hundreds of cadaver studies, creating accurate and aesthetically brilliant anatomical drawings.

As the centuries passed, images of the dead came to be created for practical, scientific purposes rather than to teach people a moral lesson about looming mortality. However, the haunting associations with death remained, and to this day we remain fascinated with these anatomical depictions of our mortal bodies.

Anatomy Drawing Torso

This study of a partially dissected male torso comes from the Venetian studio of Titian and is dated 1543. It’s a striking work, with the body posed in dramatic contrapposto (meaning, as though the weight is resting on one leg, creating a feeling of arrested motion). The intestines and other organs are arranged like draped fabric, adding to the impression of life-in-death.

This drawing from Andreas Vasilius’s 16th-century text De Humani Corporis Fabrica almost seems like a sketch of a sculpture rather than an anatomical illustration, because the heroic pose is so lifelike. The line between life and death seems awfully thin, reminding viewers that they are one footstep away from becoming just another collection of organs on display.

Unlike the memento mori art of much of the Middle Ages, this depiction of a cadaver seems strangely “alive,” making it all the more potent as a symbol of death. In creating a realistic depiction of one man’s body, Titian (or one of his apprentices) also reminds viewers that the end of that body’s life is inevitable.

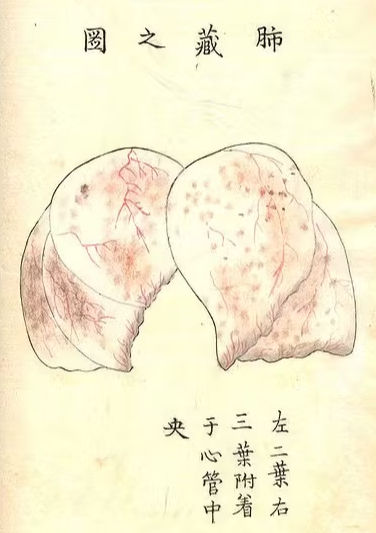

Japanese Anatomical Drawings

These images from Kaishi Hen (Analysis of Cadavers) were created in Kyoto in 1772 and feature woodcut illustrations by Aoki Shukuya. In these pages, we can see an interesting departure from the techniques of Western anatomical drawing as traditional Japanese art styles are applied to the study of various organs and bones. The result is a collection of stylized forms that sometimes resemble fruits or flowers, showing the stark beauty of the human body while creating an accurate record of its structures.

These paintings can be usefully compared to another genre of Japanese art that also flourished in the 18th century: kusozu paintings. These images show the nine stages of bodily decomposition, a grisly reminder of the inevitable processes of nature. These paintings were related to Buddhist devotional practices, meant to remind the viewer of life’s impermanence.

One famous example from the 1700s is titled “The death of a noble lady and the decay of her body.” It shows the 9th century poet Ono no Komachi in the moments before her death, and then a series of watercolors shows the various stages of bodily decomposition in a pastoral setting, linking this process with the natural world. Finally, all that is left is bones scattered in the grass.

Like the memento mori art of Europe, it encourages the viewer to set aside worldly concerns as represented by the decay of the body.

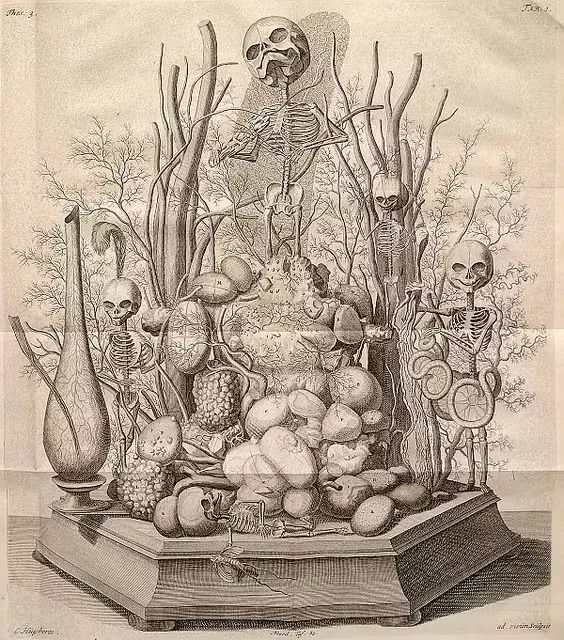

Anatomical Display

This bizarre collection of bones and other body parts blurs the line between art and anatomical drawing as fetal skeletons are arranged with preserved blood vessels and other ganglia to form a strange arrangement resembling a bouquet of flowers or a still life. It looks like something out of a haunted circus sideshow, but it’s a 1744 drawing by Dutch anatomist Frederik Ruysch.

The connection to memento mori art seems deliberate in this case, as the display recalls vanitas still lifes. The preserved body parts are clearly displayed with an eye toward aesthetics, and the drawings in Ruysch’s collection aren’t particularly useful from a medical perspective. Instead, the aim appears to be presenting anatomical items in a new and interesting way, appealing to the viewer’s sense of aesthetics as much as their scientific curiosity.

These displays are morbid and grotesque, but strangely whimsical as well, much like the danse macabre paintings of prior centuries. By juxtaposing various elements such as bones and preserved organs, they invite a fresh perspective on how we look at the body’s processes–including death.

Wound Man Illustration

The wound man is a strange and mysterious motif that appears in many 15th and 16th-century manuscripts. It depicts a human figure suffering from numerous wounds at the same time, such as being stabbed, bludgeoned, and pierced with arrows. The purpose of these images is not entirely clear, but they seem to be intended to show the effects of various wounds on the body. Sometimes they appear with medical advice written in the margins.

This particular wound man comes from a 15th-century English manuscript. The author is unknown, but it’s attributed to “pseudo-Galen,” meaning the author wanted to link it to the famous Roman physician Galen of Pergamon. This seems to indicate it’s part of a medical text.

It’s hard to escape the memento mori connotations of the wound man, since he shows in graphic detail all the ways it’s possible to be killed. One minute you’re marching through a muddy field, and the next you’re full of French arrows. At the same time, the sheer number of injuries is so over-the-top you can’t help but find it funny. Whether he’s tragically comic or comically tragic, the unfortunate wound man always leaves a lasting impression.

Muscles of the Head Illustration

This print by Jacques Fabien Gautier d'Agoty shows the muscles of the face and neck in richly saturated colors. It’s part of a collection called Myologie complete en couleur et grandeur naturelle (1746) filled with incredibly detailed depictions of the muscles of the human body. These images are so vivid and intense with their ruby reds and deep greens that they become a feast for the eyes (sometimes literally, since dissected muscles resemble, well, meat). For all their scientific rigor, these illustrations have a dreamlike quality that draws you in.

Unlike traditional portrayals of the memento mori theme featuring a skull, this human head retains expressive features, creating a haunting effect. Rather than being an anonymous depiction of a symbolic skull, it feels like a real person. Although the intention of these illustrations is educational, viewers can’t help feeling exposed as the images force us to contemplate what lies beneath our facades.

Skeleton Drawing Art

William Cheselden’s hugely influential book Osteographia or the Anatomy of the Bones (1733) features dozens of lavish illustrations of human and animal skeletons, often arranged in artistic or humorous poses. For instance, one plate shows a cat skeleton arching its back and hissing at a barking dog skeleton. Combining scientific exactitude with artistic expression, these sensitive and timeless anatomical drawings showcase the body’s bare essentials.

By the time these illustrations were created, the Enlightenment was in full swing. Gone are the moralizing memento mori overtones of skeleton art from previous centuries. Here, the bones and skeletons are presented as neutral, even beautiful. They are simply objects worthy of study and understanding.

This new era of reason, empiricism, and scientific knowledge brought widespread changes from medical advances to the French Revolution. The Enlightenment was a time of profound optimism in Europe and America, but its dark side would be realized in the bloody excesses of the political upheavals its ideas had helped to inspire.

Anatomical drawings might be more concerned with the life of the body than that of the soul, but their resemblance to memento mori art invites viewers to contemplate death just the same. Precise and detailed illustrations of human anatomy helped to propel medical science forward, while at the same time serving as a stark reminder of the way of all flesh.

This tension between scientific optimism and the morbid reality of death is what makes medical illustrations so compelling. They blur the line between science and art and show us what it means to be human–bones and all.